The Casus Belli itself

Few things in a professional environment are more important than a lasting impression; be it for building trust or conveying unappreciated quality, it is often what kills any system: people lose confidence in it. Imagine seeing something always faulty; a stakeholder sees a failed commitment. They do not see, and cannot see, the distinction between the feature that failed and the foundation it rests upon. To them, the system is monolithic; if any part fails, the whole is suspect. This perception, though technically naïve, creates social stress that technical accuracy cannot dispel.

As failures accumulate, pressure builds. Someone must be responsible, and something must be done. The organization demands resolution, not in the form of root cause analysis or targeted fixes, but in the form of visible action, decisive change; very much like a ritual of purification. The tension must be released.

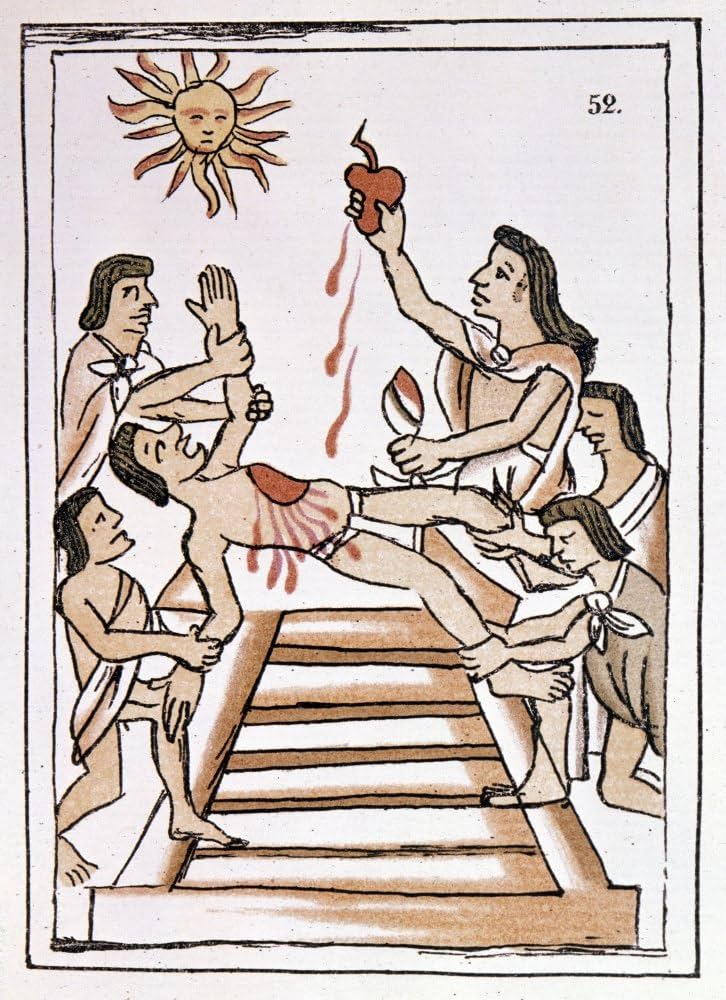

What follows is as old as human society itself: a victim is selected, the guilt is assigned, and finally, the victim is destroyed. Through its destruction, social cohesion is restored. The Aztecs sacrificed captives atop pyramids to ensure the sun would rise. We sacrifice codebases in conference rooms to ensure projects will ship. The mechanism is identical; only the altar has changed.

René Girard observed that (almost) all human communities resolve internal crisis through scapegoating: the selection of a victim to bear collective guilt, whose expulsion restores order. The scapegoat need not be guilty; it need only be acceptable as a target. Its guilt is constructed through narrative, not discovered through investigation.

Some dangerous individuals, however, institutionalize such ritualistic practices into what I call Casus Belli Engineering: the use of perceived failure as pretext to replace established systems with one's preferred worldview. The broken feature is the crisis that demands resolution. The foundation becomes the scapegoat, selected not for its actual guilt but for its vulnerability and the convenience of its replacement. And in most cases, this unfolds organically, driven by genuine belief in the narrative. These individuals are truly alchemists at heart; they have the power to manipulate the phantoms of lasting impressions to their favor. They do not wait for crisis; they nourish it. They do not stumble into scapegoating; they engineer it. They fabricate casus belli deliberately, using the ancient machinery of collective violence to remake systems in their own image. These are not confused engineers making honest mistakes in attribution. These are political operators who have discovered that technical failure can be converted into organizational power.

The danger is not the scapegoating itself; humans will scapegoat. The danger lies in those who have learned to trigger the mechanism strategically, who can reliably convert any failure into an opportunity to destroy what exists and build what they prefer. They are the high priests of a secular religion, and their rituals shape our technological landscape more than any technical merit.

An Aztec sacrifice

An Aztec sacrifice

The Scapegoat Mechanism

Girard's insight was that communities resolve internal conflict through scapegoating: the selection of a victim to bear collective guilt, whose expulsion or destruction restores social cohesion. The scapegoat need not be guilty of the crime attributed to it; it need only be acceptable as a target.

In software organizations, the pattern is identical. A failure creates tension, demands explanation, threatens careers. Rather than confront the actual causes (which might implicate recent decisions, current leadership, or systemic issues), the organization selects a scapegoat. The scapegoat must be:

-

Plausibly connected to the failure: It need not be the cause, but it must be in the vicinity. A dependency, a framework, an architectural pattern.

-

Unable to defend itself: Either because it is old ("legacy"), unfashionable ("outdated"), or championed by people who have left the organization.

-

Replaceable with something the accusers prefer: This is critical. The scapegoat's death must enable the birth of the accuser's alternative.

Once selected, the scapegoat is ritually condemned. Its guilt is established through repeated assertion. "We keep having problems because of X." The actual problems (error handling, testing, operational concerns) fade into the background. X becomes the problem. X must be destroyed.

This is what I call Casus Belli Engineering: the use of a tangential failure as pretext to replace working systems with one's preferred worldview. The broken feature is the casus belli, the justification for war. But the war's objective has nothing to do with the stated cause. The war is about replacing one paradigm with another, using failure as political cover.

The Pattern

The pattern unfolds predictably:

-

A feature breaks repeatedly. Usually because of poor integration with external systems, inadequate error handling, or environmental issues (network, third-party APIs, deployment infrastructure).

-

The feature depends on some foundational component. This component works correctly; it has always worked correctly. The failures are not caused by it. But it exists in the dependency chain.

-

Someone decides the foundational component is "the problem." Not the actual source of failures, but the foundation itself. The architecture. The paradigm. The way things are done.

-

The real failures become ammunition. "We keep having issues with X" becomes "X is built on Y and Y is the problem." The actual causes (external dependencies, error handling, testing gaps) are ignored in favor of a narrative that indicts the foundation.

-

A replacement is proposed. The replacement always happens to align with the proposer's preferred technologies, methodologies, or architectural patterns. This is not coincidence.

-

The foundation is sacrificed. Both the broken feature and its working foundation are scrapped. The broken feature "proves" the foundation was wrong all along. That the foundation worked correctly is dismissed as irrelevant; it was "the wrong approach."

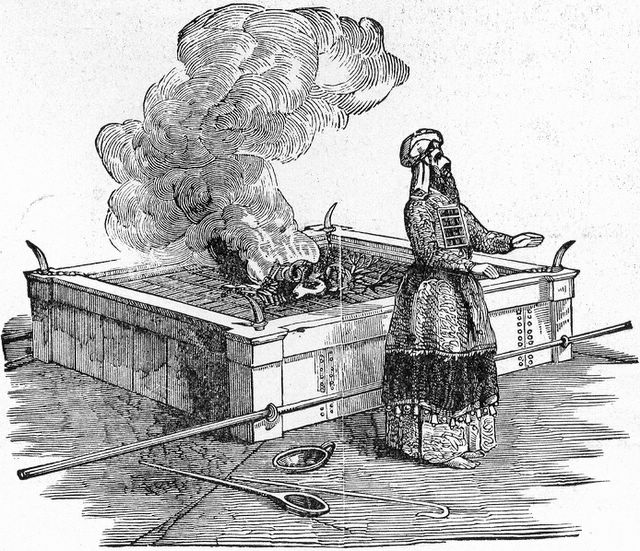

A Jewish high priest offers an animal in sacrifice

A Jewish high priest offers an animal in sacrifice

The Psychology of the Hunt

Scapegoating also requires certain social conditions: crisis, undifferentiated rivalry, and collective mimesis (imitation). Software organizations provide all three.

Crisis: The broken feature. The production incident. The customer complaint. Something has failed, visibly, and someone must be held accountable.

Undifferentiated rivalry: Multiple engineers or teams with similar status competing for influence. No clear authority on technical decisions. Everyone has opinions, few have decisive power.

Collective mimesis: Once someone frames a foundation as "the problem," others imitate this judgment. The narrative spreads. Doubt becomes consensus. What started as one person's opinion becomes organizational truth.

Into this environment steps a particular personality type. Drawing from the Rocket Model (Curphy and Hogan), you would observe that they exhibit:

Core motivations:

- Status anxiety in technical hierarchies: Not necessarily insecure about technical judgment, but acutely aware of positional competition. Sees technical decisions as zero-sum status games.

- Pattern-matching over first-principles thinking: Recognizes surface similarities and applies learned "solutions" rather than analyzing root causes. This isn't stupidity; it's cognitive efficiency gone wrong.

- Need for visible impact: In organizations where incremental improvements go unnoticed, large paradigm shifts become the only legible form of contribution. Career advancement requires "transformation," not maintenance.

Enablers:

- Genuine belief in their narrative: Not cynical operators, but true believers. They've convinced themselves first. The self-deception is complete and sincere.

- Skill at organizational navigation: High emotional intelligence, good at reading room dynamics, understand how decisions actually get made (which often isn't through technical merit).

- Impatience with complexity: Not low intelligence, but low tolerance for ambiguity and nuance. Prefer clean narratives to messy reality. "This is fundamentally wrong" is more satisfying than "this has three interacting failure modes."

Behavioral markers:

- Ideological rigidity masquerading as pragmatism: Have strong priors about "correct" architecture/methodology, but frame these as practical concerns.

- Selective evidence gathering: Not dishonest, but genuinely don't see contradicting data. Confirmation bias operates unconsciously.

- Rhetorical skill disproportionate to analytical depth: Better at presenting arguments than constructing them. Can make weak causation sound compelling.

- History revisionism: Genuinely remember past systems as worse than they were because current narrative requires it.

Organizational context that amplifies this:

- Absence of accountability for predictions: Replacements are rarely evaluated against promised improvements. The ritual provides closure regardless of actual outcomes.

- Reward structures favor "strategic thinking" over execution: Making bold architectural pronouncements is valued more than fixing actual bugs.

- Technical decisions made by committee: Diffused responsibility means narrative quality matters more than evidence quality.

A personality type that matches such descriptions is perfect for initiating the scapegoat mechanism. They have the motivation to identify a target (status anxiety in competitive hierarchies), the rhetorical skill to build a narrative (organizational navigation ability), and the psychological need to see the sacrifice through (need for visible, transformative impact). The broken feature gives them the crisis they need. Their pattern-matching over first-principles thinking prevents them from distinguishing the feature's actual causes from the foundation's perceived guilt. Their genuine belief in the narrative, combined with selective evidence gathering, ensures they will push it until it becomes consensus.

And critically, their ideological rigidity (and perhaps ontological commitment) demands that they not just propose an alternative, but destroy the existing approach. The scapegoat must die so that their worldview can be validated. This is not cynicism; they genuinely believe the old system was fundamentally wrong. The organizational context amplifies this: when technical decisions are made by committee and accountability for predictions is absent, narrative quality matters more than analytical rigor. The clean story beats the messy truth.

The Case of Agile: Industrial-Scale Scapegoating

The Agile Manifesto is perhaps the most successful example of Casus Belli Engineering in software history. It is also a perfect demonstration of Girardian scapegoating at industrial scale.

The crisis: software projects failing. Over budget, over schedule, wrong requirements, poor quality. Real problems requiring real solutions.

The scapegoat: "Waterfall"; "Heavyweight processes"; "Big upfront design"; "Comprehensive documentation"; a constellation of practices bundled together and given a name so they could be ritually condemned.

The brilliance was in the selection. "Waterfall" as a term is largely a straw man; few organizations actually practiced pure sequential development as described in the caricature. But it is plausible enough. Projects did fail. There were documentation standards. There were phase gates. The connection could be asserted, and assertion was enough. The context here matters very little for the overall narrative to be built, notice. It's as if the dotcom bubble created no actual stress that directly contributed to the social hysteria. Just like Ron Garret talks about in this article, some social pressure was slowly cultivated over the years, and terms, not ideas, had to leave the common speech:

"It is incredibly frustrating watching all this happen. My job today (I am now working on software verification and validation) is to solve problems that can be traced directly back to the use of purely imperative languages with poorly defined semantics like C and C++. (The situation is a little better with Java, but not much.) But, of course, the obvious solution (to use non-imperative languages with well defined semantics like Lisp) is not an option. I can't even say the word Lisp without cementing my reputation as a crazy lunatic who thinks Lisp is the Answer to Everything. So I keep my mouth shut (mostly) and watch helplessly as millions of tax dollars get wasted. (I would pin some hope on a wave of grass-roots outrage over this blatant waste of money coming to the rescue, but, alas, on the scale of outrageous waste that happens routinely in government endeavors this is barely a blip.)"

Ron Garret, "Lisping at JPL" 2002

The manifesto provided the ritual language for the sacrifice. It presents tautologies or straw men that obviously do not bear, at verbatim, the attributed meaning people assign to them. What they do provide is a sacrificial language that was used to pivot the collective conscience.

At verbatim, the statements sound not so profound. Has anybody ever consciously chosen processes and tools over individuals and interactions? Was it ever institutionalized? I am willing to wager some folks of that opinion do exist, mostly because I have seen them myself (claiming to be agile, comically), but they are (hopefully) the exception and deemed dysfunctional. This is a bizarre dichotomy tailored to sound like a revelation. It sounds like wisdom. It makes the listener feel enlightened for agreeing with something that seemed so evident, yet was never in dispute. All the statements do in fact bear a deeper meaning, but their presentation is made to propel dichotomies and scapegoat the words themselves. The meaning is not entirely altered from before (or after), it's just that the behavior needs to be readjusted.

These are not insights. These are accusations dressed as principles. Each one constructs in the mind a target ("processes," "documentation," "contracts," "plans") and positions Agile as the that adjudicates their degree of acceptance. The target is what we are fed up with, the practices advocated are not necessarily new; iterative development predates the manifesto by decades. What was new was the ritual.

The manifesto did not invent better practices. It provided a casus belli. It gave people permission to replace existing processes by framing those processes as the source of failure. The actual problems (poor requirements gathering, lack of customer access, inadequate testing, unrealistic schedules, management dysfunction) were not addressed. Instead, "waterfall" became the scapegoat, and killing it became the solution.

This is textbook Girardian scapegoating. The community (software industry) faced crisis (failing projects). A victim was selected (waterfall/heavyweight processes). The victim was assigned guilt through repeated assertion. The victim was destroyed (organizations abandoned existing processes). Social cohesion was restored (everyone is now "Agile"). The actual problems persisted, but the ritual had been completed. Now we are in the age of Super ICs, and all management is abhorred, cycle repeats.

Agile succeeded not because it was right, but because it performed the scapegoat mechanism perfectly. It identified a plausible enemy, constructed its guilt, and offered itself as salvation. That the enemy was largely fictional and the salvation was mostly rebranded existing practices did not matter. The ritual worked. The scapegoat died. The narrative won.

Why It Works

Casus Belli Engineering works because it exploits cognitive biases and organizational dynamics:

Availability bias: The recent failure is vivid and memorable. The years of the foundation working correctly are abstract and forgotten. The broken feature becomes the "proof" of systemic problems.

Confirmation bias: Once someone decides the foundation is wrong, they interpret all subsequent issues as validation. Successes are ignored or attributed to "working around" the foundation. Failures are evidence of fundamental flaws.

Status quo bias: Normally people resist change, but if you can frame the status quo as "failed," people become eager to change. The broken feature demonstrates failure; therefore the foundation must go. The converse is analogous in its arbitrariness; if preserving the foundation serves for the particular interests of the agent, then change itself must be avoided.

Authority and consensus: In low-trust environments, people defer to confident voices. If someone repeatedly asserts that the foundation is the problem, others will accept it rather than investigate. The narrative becomes consensus, and consensus becomes truth. In this environment, actors are more sensitive for opportunities to create their clusters of interest. This helps to cement isolated groups that, while they may not agree with each other, become open to consent with a common oppressor.

Sunk cost fallacy (avoided through replacement): Rather than fix the actual problem (which would require admitting the recent failures were addressable), replacing the foundation lets you avoid confronting sunk costs. You are not "fixing mistakes"; you are "adopting better practices."

The Damage

The damage from Casus Belli Engineering is substantial:

Good systems are destroyed. Foundations that worked, that were well-understood, that had years of refinement, are scrapped because they were adjacent to a failure. The organization loses institutional knowledge and proven solutions.

Actual problems are not solved. The broken feature's real causes (poor error handling, inadequate testing, environmental issues) remain. They will resurface in the new system, because they were never addressed.

Churn and instability. Every few years, a new broken feature provides a new casus belli. The cycle repeats. Foundations are replaced, then replaced again. Nothing stabilizes because stability is confused with stagnation.

Loss of trust. When replacements fail to solve the problems they claimed to address, trust erodes. But rather than recognize the pattern, organizations blame the new foundation and start looking for the next replacement.

Talent attrition. Engineers who understand causation, who can distinguish between correlation and root cause, become frustrated. They leave. What remains are those who excel at political maneuvering disguised as technical leadership.

Recognition and Resistance

How do you recognize Casus Belli Engineering? Look for these patterns:

The scope of the proposed solution exceeds the scope of the problem. A broken feature that fails due to external API timeouts does not require rewriting the entire service layer in a different language. If the solution is much larger than the problem, suspect ulterior motives.

The failure is used to indict a paradigm rather than a specific implementation. "This OOP code is hard to maintain" becomes "OOP is the problem." "This microservice is hard to debug" becomes "microservices were a mistake." The leap from specific to general is where the casus belli operates.

The proposed replacement aligns suspiciously well with the proposer's expertise or preferences. If the person who has been advocating for GraphQL suddenly decides that a REST API failure proves REST is fundamentally flawed, be skeptical.

The actual root causes are not analyzed rigorously. If the investigation stops at "X is built on Y and therefore Y is wrong," rather than continuing to "X fails because of Z which is unrelated to Y," you are witnessing a casus belli development.

The rhetoric emphasizes revolution over evolution. "We need to completely rethink how we do X" rather than "we need to fix this specific issue in X." Revolutionary rhetoric is a tell; it signals that the goal is replacement, not repair. Albeit necessary at times.

How do you resist it?

Insist on root cause analysis. What is the actual mechanism of failure? Not "the system is bad," but "this specific call fails because of this specific condition." Causation, not correlation.

Separate the failure from the foundation. Can the failure be fixed without replacing the foundation? If yes, why are we discussing replacement?

Demand that proposals address actual problems. Will the new approach actually solve the root causes? Or will it just move them to a different layer?

Evaluate proposals on their own merits, not as alternatives to "failed" systems. The new approach should stand on its own value, not derive value from tearing down the old approach.

Recognize psychological patterns. Is this person insecure about their technical judgment? Are they trying to validate their worldview rather than solve a problem? Motivation matters.

The Agile Postscript

Returning to Agile: what would honest advocacy have looked like?

It would have said: "We have found that iterative development with frequent customer feedback reduces requirement mismatches. Here are case studies. Here are measured outcomes. We propose adopting these practices."

Instead, we got: "Traditional development is broken. It values processes over people. It produces documentation instead of working software. We propose a new paradigm."

The first is an engineering argument. The second is a casus belli. The first might have led to thoughtful adoption of useful practices. The second led to wholesale replacement of development methodologies with "Agile" frameworks that often retained the worst aspects of what they claimed to replace (rigid processes, now called "ceremonies"; comprehensive documentation, now called "backlogs"; detailed planning, now called "sprint planning").

Agile succeeded not because it was right, but because it provided a casus belli for people who wanted to change how software was built but lacked a politically acceptable justification. The manifesto gave them that justification. The broken projects were the evidence. The methodology was the scapegoat. The replacement was inevitable once the narrative was established.

This is how Casus Belli Engineering works at scale.

A Final Observation

Girard noted that scapegoating requires collective blindness. The community must not recognize the mechanism while it operates. Once you see the scapegoat for what it is (an innocent victim bearing projected guilt), the ritual loses power. But if you believe the scapegoat is genuinely guilty, the mechanism works perfectly.

This is why Casus Belli Engineering persists. Participants do not see themselves as performing a ritual. They believe they are solving problems, making technical decisions, improving the system. The narrative feels true because everyone around them agrees. The scapegoat's guilt feels obvious because it has been asserted so many times.

The pattern continues because it is effective at what it actually does: resolve organizational tension, validate preferred worldviews and enables political change under technical cover, resulting in a collective celebration trophy that improves the group morale. That it does not solve the actual technical problems is irrelevant to its success as a social mechanism.

But once you see it, you cannot unsee it. The next time a broken feature leads to calls for replacing the foundation, you will recognize the pattern. The crisis. The scapegoat. The false causation. The preferred alternative waiting in the wings. The ritual language of condemnation.

And you will face a choice: participate in the ritual, or resist it.

Resistance is difficult. It requires insisting on causation when narrative is more compelling. It requires defending systems that have been marked for death. It requires being the person who "doesn't get it," who "resists change," who "ponders well the status quo."

But resistance is engineering. Engineering is about understanding what actually causes what, about making targeted improvements based on evidence, about distinguishing correlation from causation even when the narrative is seductive.

Casus Belli Engineering is not engineering. It is politics disguised as engineering, ritual disguised as analysis, scapegoating disguised as problem-solving.

We should choose engineering. Even when the ritual is more socially desirable. Even when the scapegoat has already been selected. Even when everyone else has agreed on the narrative.

Especially then.